Evidence from a mass vaccination campaign for an outbreak of bacterial meningitis in New Zealand had unexpected results: reduced rates of the sexually transmitted disease gonorrhea, a study published Monday in the journal The Lancet finds. It is the first time a vaccine has shown any protection against gonorrhea.

Scientists say the results provide fresh inspiration for developing a specific vaccine against the STD, which causes about 78 million new cases worldwide each year.

In recent years, gonorrhea has shown increasing antibiotic resistance, with some patients unable to be treated with any available drug. Because of this, the World Health Organization includes gonorrhea in its list of bacteria that pose the greatest threat to human health.

“The emergence of completely drug-resistant gonorrhea is a major concern,” Dr. Helen Petousis-Harris, lead author of the new study and a senior lecturer at the University of Auckland, wrote in an email.

She explained that “even moderate protection” against the sexually transmitted disease could have significant impact because the bacteria that cause it “are very tricky.” They develop resistance to drugs by transferring genes in atypical ways and recombining with related bacterial species.

“Given the emergence of drug resistance, a vaccine may be our only avenue,” Petousis-Harris said.

‘Cousin’ bacteria

“In the early 2000s, there was a large epidemic of meningococcal B disease in NZ. The disease rate was very high, and it was affecting a lot of people,” said study co-author Dr. Steve Black of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital. In the absence of a vaccine, the government requested help from the WHO to “tailor-make” one.

Meningococcal disease, the bacterial form of meningitis, is a serious infection of the meninges, the membrane covering the brain. It’s transmitted from person to person, usually in close contact, such as kissing, sneezing or coughing, or living in close quarters with an infected person.

“Meningococcal B disease is very lethal disease, and even people who survive are left with a lot of lifelong medical problems,” Black explained.

A vaccine targeting the specific strain of bacteria causing meningococcal disease in the New Zealand outbreak was eventually “developed in a collaboration between Chiron Vaccines, the National Institute of Public Health of Norway (NIPH) and the New Zealand government,” according to Mary Anne Rhyne, director of corporate communications at GlaxoSmithKline, the pharmaceutical company that inherited the vaccine from Chiron through a series of corporate acquisitions.

The vaccine targeted the vesicle, or sac, on the outer membrane of the bacteria.

Beginning in 2004 and lasting through 2006, a mass vaccination campaign inoculated most of the New Zealand population: about 90%, including 81% of those under age 20. New Zealand scientists then published their results for the impact of the vaccine on the outbreak.

“I wondered, in looking at their results from the outbreak, if there was any possibility that this vaccine might have had any other effects,” said Black, who focused on the country’s gonorrhea statistics in particular.

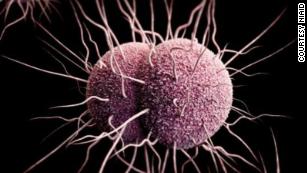

Neisseria gonorrhoeae bacteria (which cause gonorrhea) and Neisseria meningitidis bacteria (which cause meningococcal disease) are “two related organisms. They’re cousins, if you will,” he said, explaining that the genetic makeup of the two is “85 to 90% similar.”

Seeing how rates of gonorrhea fell after the vaccination campaign, Black knew that a scientific study of his theory needed to be done.

Petousis-Harris and her co-researchers, who had access to a database recording events during the meningococcal B outbreak, set to work testing his hypothesis.

“We compared the vaccination rates in two groups of people,” Petousis-Harris explained. One group had gonorrhea, and the other group had chlamydia, both of which are spread through sexual contact.

If the vaccine had an effect against gonorrhea because it is an organism related to meningococcal disease, the researchers hypothesized, then no effect should be seen against chlamydia, an unrelated organism.

“This is exactly what we saw,” Petousis-Harris wrote in an email. “We found that people with gonorrhoea were less likely to be vaccinated than people with chlamydia,” indicating that the vaccine protected against gonorrhea but not chlamydia.

The researchers also discovered that vaccinated people were significantly less likely to become infected with gonorrhea than people who had not received the vaccine: 41% vs. 51%.

Taking other factors into account, including ethnicity and gender, the researchers concluded that having received the meningococcal vaccine reduced the incidence of gonorrhea by about 31%.

Still treatable, but resistance rising

Virginia Bowen, an epidemiologist in the Division of STD Prevention at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said that in 2015, there were more than 390,000 reported cases of gonorrhea in the United States. This is a 13% increase from the previous year.

“It is estimated that more than 800,000 new infections occur every year, but because gonorrhea can be symptom-less, fewer than half of all new infections are diagnosed,” she said, explaining that untreated cases can cause serious problems, including conditions that lead to infertility in both men and women.

“For women, it can increase their risk for a life-threatening ectopic pregnancy,” Bowen said. “Untreated gonorrhea can also increase a person’s risk of acquiring or transmitting HIV.”

Gonorrhea is still treatable in the US, said Bowen, though resistance to the current antibiotics may develop.

Scientists with pharmaceutical companies are working to develop a vaccine specifically against the infection.

The New Zealand vaccine is no longer licensed, but the membrane-attacking component has been included in the formulation of Bexsero, GlaxoSmithKline’s meningococcal vaccine. Bexsero is made to offer broader coverage by fighting more strains than the original.

“These findings are encouraging,” Rhyne said. “The next step for GSK is to further explore and understand the potential of Bexsero to help protect against (gonorrhea).”

Petousis-Harris said the investigation also found the vaccine to be protective against gonorrhea hospitalizations.

Black said this suggests that the vaccine, which was effective against mild infections, may be more effective against the more severe cases.

Gonorrhea, noted Black, is in all countries. “This is really a universal issue,” he said. “It doesn’t kill, but it maims.”

Comments are closed.